FREE DOWNLOAD

Hard-learned leadership lessons from both the military and the corporate world

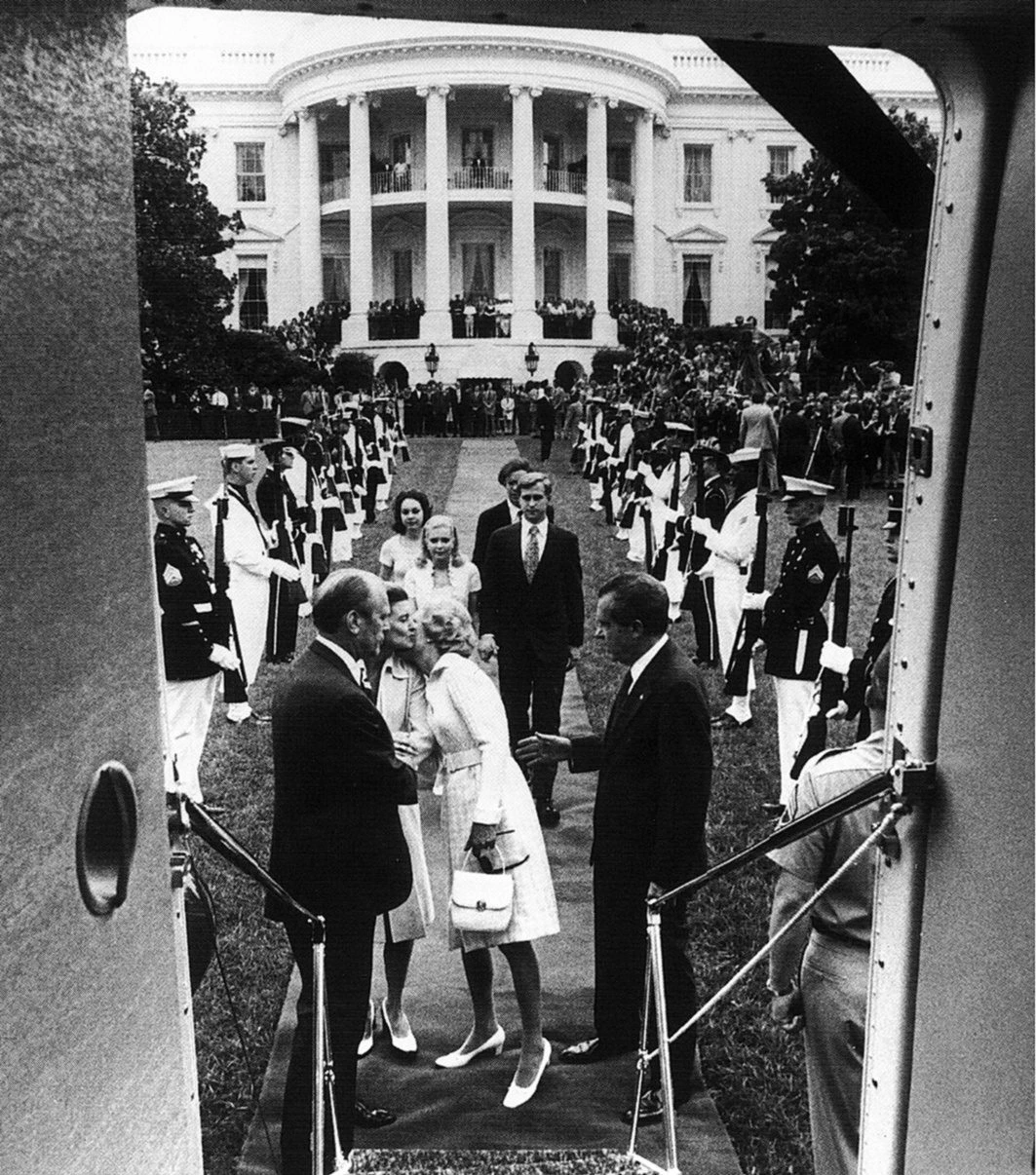

Historical Leadership Lessons: Watergate

Not All Lies Are Equal: Leadership Lessons from Nixon and Watergate

In June 1972, individuals working for President Nixon’s re-election campaign were arrested while attempting to wiretap the Democratic National Committee’s offices. What followed was not handled through legal transparency. Instead, officials close to the President took coordinated steps to delay investigations, mislead the press, and redirect federal agencies. These were not improvised acts under pressure. They were purposeful responses, built on a view that preserving political capital took precedence over the rule of law.

The scandal began with calculated decisions to withhold, obscure, and interfere. Leadership, in this context, was no longer about guiding a nation. It had turned inward, focused on controlling exposure and deflecting inquiry. That shift in intent is where the lessons begin.

Lesson 1: Integrity Requires Infrastructure

Nixon’s administration had no shortage of public language around honour, national service, and duty. Internally, however, behaviour did not reflect those commitments. Strategic discussions centred on how to suppress accountability, not uphold it.

Organisational integrity depends less on slogans and more on what is permitted, prioritised, and tolerated. A leader’s stated values mean little if the structures beneath them—hiring practices, response mechanisms, systems of accountability—are not aligned. When decisions are repeatedly shaped by short-term interests, ethical erosion is not an accident. It becomes routine.

Lesson 2: The Environment Around the Leader Becomes the Standard

Inside Nixon’s White House, there was a shared understanding that challenges to the dominant view were not welcome. Unquestioned loyalty became a kind of qualification. Internal culture rewarded discretion, discouraged dissent, and fostered mistrust.

This environment was not declared outright. It emerged from subtle cues: who advanced, who was removed, which voices were heard. In any leadership setting, silence can be a signal. When leaders consistently avoid open dialogue or punish difference, they shape behaviour without needing to articulate rules. Over time, individuals stop bringing forward risk, alternative thinking, or unwelcome truths, not because they were told not to, but because they learned not to.

Lesson 3: Loyalty Without Boundaries Invites Collapse

Many of those involved in the Watergate cover-up justified their actions as loyalty to the President. They withheld information, misled investigators, and facilitated payments that obstructed justice. Few considered the broader implications for the institutions they served.

Loyalty in leadership cannot be defined by personal alignment alone. It must be accompanied by clarity of responsibility and an understanding that public roles require adherence to standards beyond internal allegiance. When the team is encouraged—explicitly or not—to protect the individual over the mission, failure becomes systemic.

Lesson 4: Efforts to Contain Truth Increase Risk, Not Control

Nixon’s approach to the unfolding scandal was to centralise information, reduce external access, and monitor his environment closely. This included installing a voice-activated recording system inside the White House, which ultimately captured conversations that confirmed efforts to obstruct justice.

The desire to tightly manage perception, information, and outcomes is not unusual among leaders. But doing so at the expense of transparency tends to shorten the time before internal problems become public crises. What appears contained may be poorly understood, and therefore more vulnerable. In this case, the very tools used to monitor risk produced the evidence that brought down the presidency.

Lesson 5: Leadership Is Tested Most When Outcomes Are Unfavourable

The original incident—a break-in by political operatives—was significant, but not unmanageable. The greater damage came from the consistent refusal to engage with it honestly. Efforts to suppress information prolonged the issue, deepened public distrust, and involved more individuals in wrongdoing.

Errors are inevitable. A leader’s response to those errors determines whether they remain setbacks or become structural threats. If every problem is approached as something to be hidden, the organisation’s capacity for resilience diminishes. Addressing fault early reduces institutional cost—both in terms of credibility and function.

Lesson 6: Trust Is Not a Resource—It’s a Condition

After Watergate, public trust in government institutions declined significantly. The change was not only visible in polling numbers, but in the nature of governance itself. Oversight increased. Presumptions of good faith were replaced by adversarial review. The pace of decision-making slowed, and the space between leaders and those they served widened.

For any leader, trust is less a reward than a prerequisite. It shapes the efficiency of decisions, the legitimacy of strategy, and the cohesion of teams. Once it begins to deteriorate, everything else becomes harder to execute. Rebuilding it takes time and sustained consistency, often more than one leadership cycle can offer.

Lesson 7: Ethical Decline Is Often Incremental

Watergate did not emerge from a single outrageous act. It developed through a pattern of decisions that, when isolated, seemed manageable. When viewed together, they formed an architecture of deception. Each compromise led to the next, not because it was inevitable, but because earlier actions had gone unchallenged.

This is a familiar pattern in leadership. When leaders begin to view rules as flexible under pressure, and when each boundary crossed is treated as situational rather than consequential, organisations drift. Over time, the original mission is lost, replaced by the task of maintaining the appearance of control.

Lesson 8: Stepping Down Ends a Tenure, Not Its Consequences

Nixon’s resignation in 1974 was a response to political inevitability, not moral clarity. It brought a formal end to his presidency, but the effects of his leadership decisions extended well beyond that moment. Public cynicism increased. Legislative reforms were introduced. Confidence in the executive office did not recover quickly.

Resignation can bring resolution to a crisis, but it does not automatically restore confidence. The conditions that produced failure often persist in institutional memory. Future leaders are measured not only against their own actions, but against what their predecessors allowed to unfold without consequence.

Conclusion: Leadership Without Accountability Invites Isolation

Watergate remains one of the clearest examples of leadership failure at the highest level of government. The lessons it offers are not confined to politics. They apply to any setting where authority meets ambiguity, where internal culture influences public outcome, and where leaders must choose between protection and principle.

What defined Nixon’s downfall was not ideology or strategy. It was the repeated decision to avoid accountability. That pattern—delaying, denying, redirecting—eventually closed off any viable path to resolution. The presidency did not collapse in one moment. It weakened every time the truth was deferred.

Today’s leaders operate in different contexts but face similar tests. The instinct to manage optics, protect image, or insulate from criticism remains strong. But Watergate reminds us that the cost of those decisions accumulates—and that leadership cannot function sustainably when trust is treated as expendable.

When the public, the team, or the institution begins to question whether truth still holds value inside the organisation, it is already too late to fix with a statement or a gesture. Leadership requires more than the ability to inspire. It requires the discipline to face what others would rather avoid.

Newsletter Signup

Topics

Share this post

You might also like

(07) 2114 9072

Drawn from lessons learned in the military, and in business, we make leadership principles tangible and relatable through real-world examples, personal anecdotes, and case studies.

© Copyright 2023 The Eighth Mile Consulting | Privacy